1.2 Parsing the Exam Papers

One of the biggest technical feats of this project was parsing the exam papers. The exam papers from NUI Galway were all stored in PDF format which made it a particulary hard task to approach.

PDF Format

The PDF format specification is 22 years old and is entirely backwards compatible. That means any features supported in version 1.0 of the specification are still supported the current version, 1.7. This is good for users of the PDF format because even the oldest PDFs will still work however not for developers who want to use the contents of the PDF. The format is full of old concepts, quirks and dead techniques that have plagued anyone attempting to peek under the hood. Luckily for this project, the PDF format was never accessed directly but through libraries in Python. Some libraries reviewed:

- PDFMiner - A full suite of amazing tools for parsing everything about a PDF however documentation is next to nil which makes it's a non-viable candidate.

- Slate - A very simple library that will load the PDF and extract the text (based on PDFMiner).

Some external tools were also tested:

- pdftotext - Command line tool to extract the text contents of a PDF by the Poppler project.

- pdftohtml - Another command line tool that converts a PDF to HTML (or XML).

- Tesseract - An Optical Character Recognition (OCR) library to extract the contents of the PDF.

However easy it was to access the data, one fact remains: PDF is only about presentation, not structure. The outputted data was not easy to parse. Content extracted via the libraries and tools was unstructured and unformatted. Tables, math formula, question indexes, titles and event text decoration would all corrupt the output.

Parsing the PDF contents

Structure of the exam paper

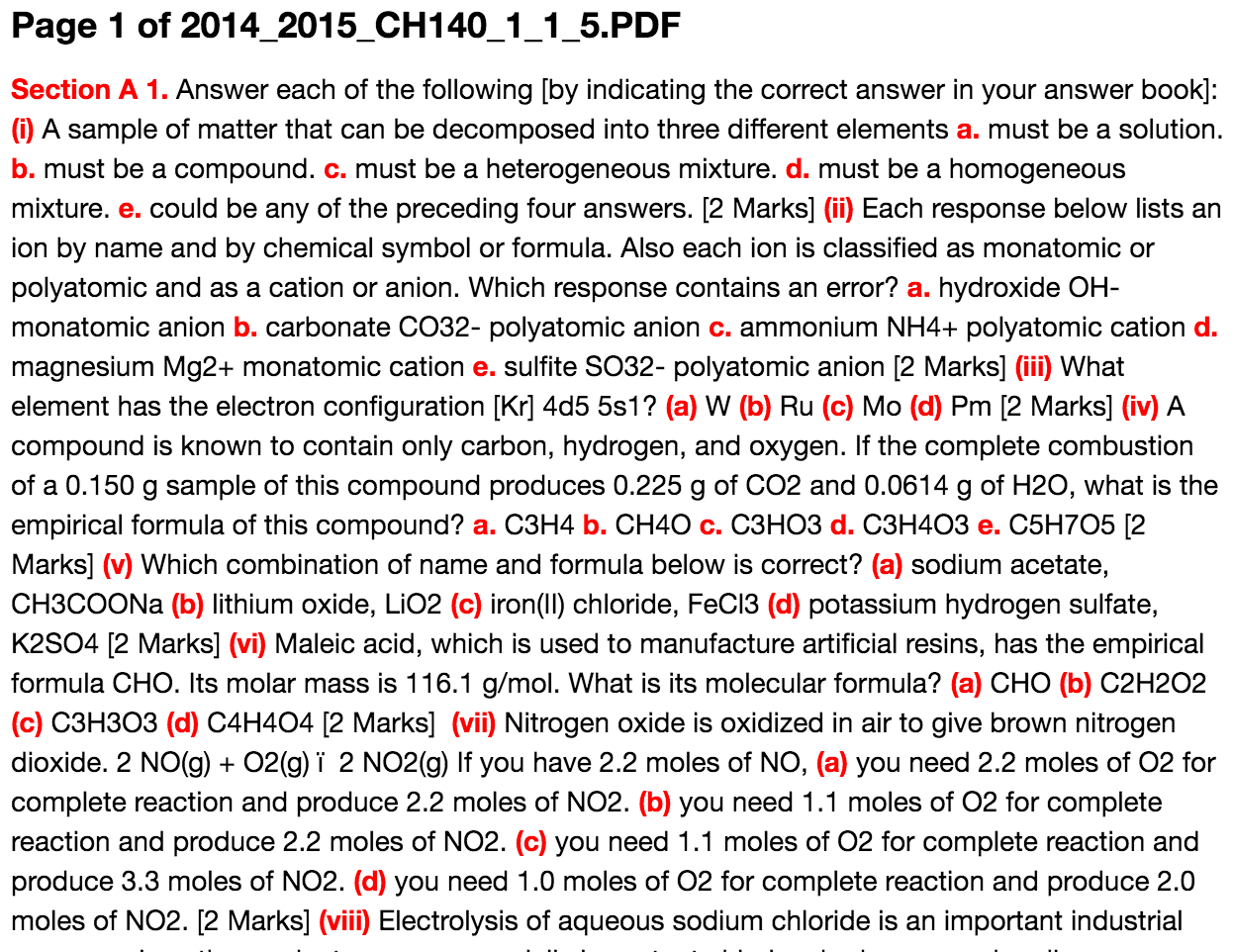

Before starting to extract the data from the PDF, the structure of the underlying data must be understood. From tests across multiple papers, no consistent structure was observed over the exam papers. Below are some observations of consistencies and inconsistencies between papers.

Consistencies between exam papers

- The first page in an exam paper described the exam paper itself. It contained metadata on the years, examiners, lecturers and classes.

- Each page in an exam paper had a page number in the footer.

Inconsistencies between exam papers

- Exam paper metadata did not have any discernable structure and the labels could appear in any order or not at all.

- Exam questions could appear indexed numerical, alphabetical and using roman numerals. e.g.

a, b, cori, ii, iii. - Exam question indices did following any formatting style. Indices could be any of the following form:

(a),(a.),(1).,[i],iii.,B.,1.,Q1.,Question 2, or just the index itself,c. - Some exam papers used sections while others did not e.g.

Section A. - Some exam papers displayed marks after each question while others did not.

- Exam papers displayed marks using square brackets

[10]or parenthesis(10). Some also included the labelmarks. - Sub-questions and multiple-choice answers would be indexed in the same format and style. e.g.

1. 1.instead of1. a.. - Sub-questions and multiple-choice answers wouldn't be indexed at all.

- Some exam questions were indexed improperly or ordered wrong. e.g.

1., 2., 4., 5., 6.. - Exam papers could be written by two or more people who each chose they own style of formatting. These exam papers had multiple, inconsistent styles between questions.

Extract indices with a Context Free Grammar

The main attempt at parsing the contents of the PDF to extract the exam paper's structure and all it's questions was via a Context Free Grammar (CFG). The grammar was used to extract the indices of each question and therefore build a usuable representation of the paper structure from the indices. The CFG was created using the Pyparsing library that allowed for constructing complex grammars using simple syntax.

The grammar was constructed to extract all the indices from the paper. It was designed to be as loose as possible to include all the types of indices (alphabetical, numerical, roman) and all their formats (square brackets, parenthesis). Whitespace and sections were also accounted for within the grammar.

import pyparsing as pp

# The exam paper CFG

_ = (pp.White(exact=1) | pp.LineEnd() | pp.LineStart()).suppress()

__ = pp.White().suppress()

___ = pp.Optional(__)

____ = pp.Optional(_)

# Define tokens for numerical, alpha and roman indices

# Max two digits for numerical indices because lecturers aren't psychopaths

index_digit = pp.Word(pp.nums, max=2)\

.setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: [Index("decimal", int(t[0]))])("[0-9]")

index_alpha = pp.Word(pp.alphas, exact=1)\

.setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: [Index("alpha", t[0])])("[a-z]")

index_roman = pp.Word("ivx")\ # We only support 1-100 roman numerals

.setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: [Index("roman", t[0])])("[ivx]")

index_type = (index_digit | index_roman | index_alpha)("index")

# Define token for ("Question" / "Q") + "."

question = (pp.CaselessLiteral("Question") + pp.Optional("."))("question")

# Define tokens for formatted indices e.g [a], (1), ii. etc.

index_dotted = (

index_type + pp.Literal(".").suppress()

).setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: t[0].setNotation("dotted"))

index_round_brackets = (

pp.Optional(pp.Literal("(")).suppress() + index_type + \

pp.Literal(")").suppress()

).setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: t[0].setNotation("round"))

index_square_brackets = (

pp.Literal("[").suppress() + index_type + \

pp.Literal("]").suppress()

).setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: t[0].setNotation("square"))

index_question = (

pp.Word("qQ", exact=1).suppress() + \

pp.Optional(".").suppress() + index_type + \

pp.Optional(".").suppress()

).setParseAction(lambda s, l, t: t[0].setNotation("question"))

# Define final index token with optional

# question_index token before formatted index

qindex = (

# Whitespace is required before each index

# (e.g. "hello world." the d. would be take for an index)

_ + \

# Optional "Question." before

pp.Optional(question + ___).suppress() + \

# The index

(index_question | index_dotted | \

index_round_brackets | index_square_brackets) + \

# Required whitespace *after* index

_

)

# Define a section header

section = (

pp.CaselessKeyword("Section").suppress() + \

__ + index_type + _

).setParseAction(

lambda s, l, t: [t[0].section()]

)("section")

# Entry point for the parser

entry = section ^ qindex

The grammar was made up of a set of tokens. Each token is made up of literals (strings) or other tokens. The gramar had three tokens to define an index itself: index_digit, index_alpha and index_roman and a final index_type that combined the three to match all. It then defined three more tokens for the index formatting style in that wrapped the index_type, one for parenthesis (( index_type )), square brackets ([ index_type ]) and the dotted form (index_type .). Those style forms were then combined to create qindex token which also accounted for an optional prefix of Q or Question in the index. For something to be an qindex, it had to have whitespace before and after the matched token. This was to prevent matching numbers or symbols mid-question. The second last token then was a section which combined the literal "Section" and index_type. Finally, the entry point for the grammar was to match either a section or qindex.

When the grammar was run on the input text from the PDF, it iterated over each character in the text and checked if that character matched the entry token, it ran the parser action for each token. These parser actions are defined using the method setParseAction on the rule and passing a lambda function with parameters containing information about the matching rules. Any return value from those actions replace the match from that rule. Also notice in the grammar above, some rules output could be surpressed by calling the surpress method which dropped that rule from the match.

The parser actions for the above tokens created Index objects for index_type which attributes were modified as they matched other rules. Eventually, the results returned an array of Indexs with contained the index type (alpha, decimal, roman), the formatting style (dotted, round, square) and whether is was a section or prefixed with a Question.

There were some major caveats to the parser:

- Sentences ending with a digit and period are picked up as indices.

- General formatting or referencing another question within a question are picked up as indices.

- Some formatted math are picked up as indices e.g.

x * (y). - Some mark forms at the end of questions are picked up as indicies.

- The PDF format usually botched the whitespace from the text leaving some indices without enclosing whitespace and therefore not included as an indice.

Creating the question tree

The grammar was useful for extracting the indices however the data returned from the grammar unprocessed is useless. It's the content between the indices, the questions, is what the project is after.

The exam papers are based on a heirarchy, with usually three to six top level questions and many sub-questions. The best data structure for this type is obviously a tree. Once the parsing is completed and we have a list of our index tokens, we need to put them into this tree.

index = token[0] # The incoming index

logging.info("0. Handling index %r" % index)

# If the container is the paper, just push the question

if len(index_stack) == 0:

logging.info("1. Pushing top level index %r." % index)

question = push()

continue

last_index = index_stack[-1] # The last index is the last item in the stack

if index.isSimilar(last_index): # Comparse index types e.g. "alpha" == "alpha"

logging.info("1.1 Similiar indexes %s and previous %s." % \

(index.index_type, last_index.index_type))

if last_index.isNext(index): # Determine whether is the next index

logging.info("1.1.1 Pushing index with same type" + \

" as last index and in sequence.")

pop()

question = push()

else:

logging.info("1.1.2 Question with similar indexes " + \

"but not in sequence, ignoring.")

continue

else:

logging.info("1.2 Dissimilar indexes %s and previous %s." % \

(index.index_type, last_index.index_type))

parent_index, n = None, 0

# Go through the stack (traverse the tree level) and find the similar index

for i, idx in reversed(list(enumerate(index_stack))):

if idx.isSimilar(index):

parent_index, n = idx, i

break

# No similar sibling found, We need to look up

# the stack (traverse up the tree) and see if

# we can find a similar index

if parent_index:

logging.info("1.2.1 Index similar to parent index %d up the stack [%r]"\

% (n, parent_index))

# If we have found a similar index and they're in sequence,

# it means we have found the current indexes sibling. Add the

# question after the found container.

if parent_index.isNext(index):

logging.info("1.2.1.1 Index in sequence, pushing into stack.")

index_stack = index_stack[:n]

question_stack = question_stack[:n]

question = push()

else:

logging.info("1.2.1.2 Index not in sequence, ignoring")

continue

# If we encounter a new type of index and

# it's not the start of a new list, we can just discard

# it (it's probably marks). However if the previous index is

# a section, we can just continue.

elif index.i == 1 or last_index.is_section:

logging.info("1.2.2 Pushing new question %r." % index)

question = push()

else:

logging.info("1.2.3 New index value not first in sequence, ignoring.")

continue

# Save the text between the previous indice and the current

if last_question != None:

last_question.set_content(None, pages[marker:start])

last_question = None

marker = end

elif marker == 0:

marker = end

last_question = question

This algorithm would approach the tree creation using a stack. The stack contains all the questions in the heirarchy for the current index i.e. the tail of the stack is the parent of the current index (if appropriate). The above is the content of the loop and performs the following checks for each token.

For each index:

- If the stack is empty, this must be a top level index. Push to stack with contents.

- If the tail question's (in the stack) index if of a different type to index, push to stack. Assume sub-question.

- If the tail question's index if of the same type as index push the current question and contents to the tail question's parent as sibling of the tail question.

Other checks are in place for pushing to root level parents (i.e. non-existant) and indexes that are out of sequence to their siblings. The tree builder would also save the contents of each questions to it's index.

Section A

-- 1

---- i

------ a

------ b

------ c

------ d

------ e

---- ii

...

-- 2

---- i

---- ii

---- iii

------ a

------ b

------ c

------ d

---- iv

-- 3

---- i

---- ii

---- iii

---- iv

---- v

-- 4

---- i

---- ii

------ a

------ b

------ c

------ d

---- iii

0. Handling index Index[type=alpha, value=d, i=4, section=False, notation=round]

1.1 Similiar indexes alpha and previous alpha.

1.1.1 Pushing question with same index type and in sequence.

0. Handling index Index[type=roman, value=iv, i=4, section=False, notation=round]

1.2 Dissimilar indexes roman and previous alpha.

1.2.1 Index similar to parent container index -2 up the stack [Index[type=roman, value=iii, i=3, section=False, notation=round]]

1.2.1.1 Index in sequence, pushing into parent container's container.

0. Handling index Index[type=alpha, value=a, i=1, section=False, notation=dotted]

1.2 Dissimilar indexes alpha and previous roman.

1.2.2 Pushing new question into container Question[Index[type=roman, value=iv, i=4, section=False, notation=round], questions=0].

0. Handling index Index[type=alpha, value=b, i=2, section=False, notation=dotted]

1.1 Similiar indexes alpha and previous alpha.

1.1.1 Pushing question with same index type and in sequence.

0. Handling index Index[type=alpha, value=d, i=4, section=False, notation=round]

1.1 Similiar indexes alpha and previous alpha.

1.1.1 Pushing question with same index type and in sequence.

...

0. Handling index Index[type=alpha, value=c, i=3, section=False, notation=round]

1.1 Similiar indexes alpha and previous alpha.

1.1.1 Pushing question with same index type and in sequence.

0. Handling index Index[type=roman, value=i, i=1, section=False, notation=round]

1.2 Dissimilar indexes roman and previous alpha.

1.2.1 Index similar to parent container index -2 up the stack [Index[type=roman, value=ii, i=2, section=False, notation=round]]

1.2.1.2 Index not in sequence, ignoring

0. Handling index Index[type=roman, value=ii, i=2, section=False, notation=round]

1.2 Dissimilar indexes roman and previous alpha.

1.2.1 Index similar to parent container index -2 up the stack [Index[type=roman, value=ii, i=2, section=False, notation=round]]

1.2.1.2 Index not in sequence, ignoring

Right: The outputted tree without the question content.

Results

The algorithm was tested on a wide vareity of papers to best encapsulate the variations in formatting. Courses related to Math, Chemistry and Engineering were among those tested to ensure the greatest diversity. The output was compared manually and a measure of performance was estimated.

The results were poor. The exam papers were just too inconsistent in their formatting and output for it to perform reliably. Many indices were missing the structure of the paper was almost always wrong. This was a disappointing result given the amount of effort put into the algorithm however it forced innovation in other areas to ensure the correct data was collected. Since the CFG method proved fruitless, a smarter system would be required to automatically parse the exam papers accurately. This is where some experimentation with Machine Learning entered the picture.

Data collection for Machine Learning

It was clear something smarter was required and going down the route with machine learning, especially since it's used in other parts of the project, seemed like a great option. However, to being learning models and algorithms, the project needed data. It would be impossible to train (never mind test the algorithm) without large amounts of data. Currently, there was no way of collecting the data aside from grinding away at a spreadsheet.

In the end, the decision was made to create a user interface to help parse the exam papers. This served two purposes:

- A quick method of parsing the exam papers while the automated system is being constructed.

- A method of training data collection from the exam papers.

Benefits of the user interface

- The user interface (UI) is useful to help collect data in a consistent manner by forcing a schema on the collected data.

- Allows for crowd-sourcing the contents of the papers.

- Lot faster than manually opening the exam paper's PDF file and collecting data in a spreadsheet.

The UI does have it's drawbacks however. The process is not automated being the greatest. This makes it slow and tedious in comparasion. Fortunately for the project however, once the data has been collected from the exam paper, that's it complete. There is a finite set data and it's just a matter of which method is going to win the race.